Walter Cooper ’50’s lifetime of bringing together science, education, and activism

How does one even begin to capture the essence of this leader’s lifelong impact on science, education, civil rights, and humanity? Especially when he has crossed paths along the way with the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Eleanor Roosevelt and Robert Kennedy?

Or, as a visionary leader, has helped to guide the grand visions of statewide education and educational institutions, started new churches and activist organizations across the world, contributed to new science and innovation, and influenced the lives of possibly thousands of students looking for greater purpose, direction and change in a turbulent, unfair world?

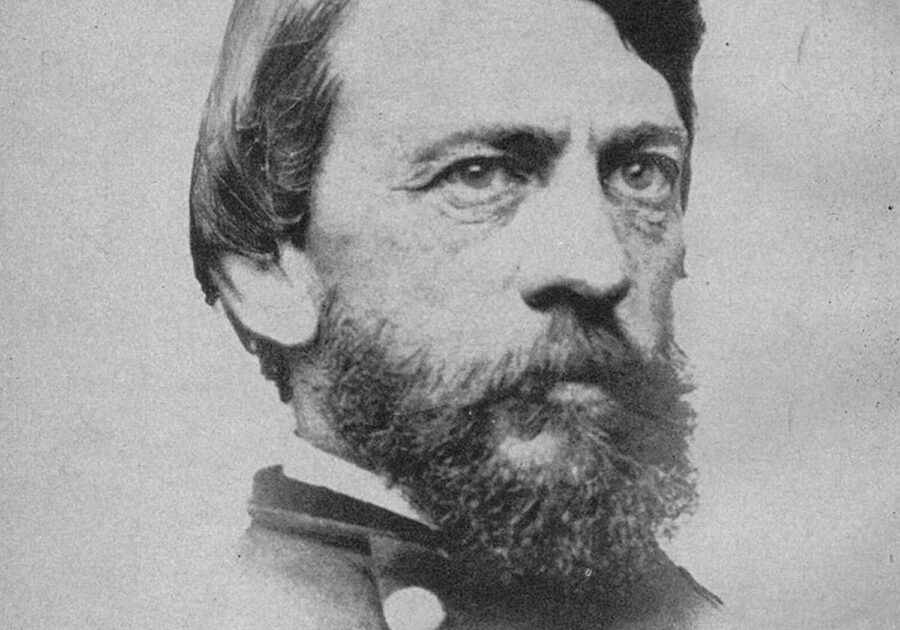

When Washington & Jefferson College invited alumnus and trustee emeritus Walter Cooper ’50, Ph.D., to the campus this past fall to honor his legacy by renaming a student residence hall after him, Dr. Cooper graciously attended a private ceremony with W&J dignitaries. Then he joined those leaders at the entrance of the former Beau Hall to unveil the new name.

But as those dignitaries walked through the building’s newly renovated common area – designed to honor this storied W&J graduate, star athlete, activist and leader, Dr. Cooper sat in a chair beneath his newly hung portrait and earnestly focused his attention on a young, African-American student sitting across from him.

Despite the celebratory distractions of the morning, the two engaged in a brief conversation about life, her ambitions, the history of an African-American church in her native Philadelphia, and his work with the African country of Mali to establish a Sister City program in the city of Bamako. Moments like these offer a glimpse of the essence of this 92-year-old’s character and legacy as a lifelong steward of science, education, civil rights and humanity.

“My father is always interested in who other people are and treating others with respect and dignity,” says Brian Cooper, Ph.D., Cooper’s 62-year-old son and an attendee of the October ceremony and building tour.

“He always has been really interested in going beyond the basic ‘how are you doing?’ and hoping they would flourish. He’s pretty amazing. I take inspiration from him, as he’s kind of a daunting example. I’m not going to fill his shoes.”

Nobody will be filling his shoes anytime soon, if Dr. Cooper can help it. He remains active in his adopted home of Rochester, N.Y., still driving civil rights and championing education as the path to racial equality and a unified and shared human experience.

“All things that live must move,” says Dr. Cooper, laughing from his Rochester home at his continued busyness even today, despite his age.

Adds Brian Cooper about his father’s life mission: “He’s always active – he doesn’t slow down. He just keeps on going.”

RACE AND THE STUDENT-ATHLETE

Dr. Cooper grew up in Clairton, Pa., in southwestern Pennsylvania’s Monongahela Valley. Upon graduating from W&J in 1950, he attended graduate school at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he met Helen, his late wife of almost 52 years. He then went to the University of Rochester, where he became the first African-American student at the school to earn a Ph.D. in physical chemistry. He has remained in the Rochester area since, enjoying a 30-year career as a research scientist and innovator at photographic technology giant Eastman Kodak while also leading civil rights activities, with better education as their foundation.

As W&J President John C. Knapp, Ph.D., says, “Dr. Cooper’s remarkable legacy spans nine decades, but his passions still lead back to Washington & Jefferson College.”

Dr. Cooper graduated from high school in Clairton in 1946 and was named “All-Monongahela Valley” for his football prowess in that same year. Another local university offered him a full academic scholarship but wasn’t going to be able to offer him an opportunity to play football, a talent which he had hoped would lead to additional scholarship funds for room and board.

Dr. Cooper describes his meeting with an admissions official at that university as going well until he asked about athletic opportunities.

“He flushed, and I knew something was wrong,” Dr. Cooper recalls of the official. “He said the university’s football schedule included some southern schools. If they had a colored student on their team, the other schools would cancel the games.”

Dr. Cooper respectfully declined the academic scholarship – and the school, not ready to give in to segregation and the systemic racial inequalities of the day. But he didn’t let racism dampen his desire to get an education and to stay on the field.

Fortunately, Dr. Cooper had befriended Dan Towler ’50, an African-American who had played high school football in the Mon Valley town of Donora.

Towler, who later went on to play professionally for the Los Angeles Rams, convinced Dr. Cooper to apply to W&J. He did and received a full academic scholarship, as well as an athletic scholarship. And he joined the Presidents football team.

“When I left home, I had $60 in my pocket, three pairs of Levi’s, my sister’s luggage, and my parents’ prayers,” Dr. Cooper says.

Dr. Cooper always had been interested in science, but he chose chemistry as his major at W&J because “I didn’t know any black chemists, so I looked at it as a challenge.”

Cooper roomed with Towler in Hays Hall, suite 518. In the off-season, he worked in the cafeteria to help pay for room and board. He studied hard and eventually became president of W&J’s National Honor Society.

“As a student, this was a continuation of the discipline process I grew up with, which was to learn as much as I possibly could,” Dr. Cooper says, illustrating his belief that a good education will help improve the human experience and transcend racial inequality.

GROWING UP POOR – AND “RICH” – IN A MULTICULTURAL COMMUNITY

Dr. Cooper says he learned his educational self-discipline, along with his broader, less-racially divided views of humankind, from his parents and neighbors in what he describes as a multicultural community that included immigrants from Italy, Sicily, Hungary, Poland, and Russia among other countries. Most men worked either in the coal mines or steel mills, as Dr. Cooper’s father did, or in small businesses that served the community.

“We were surrounded by what I consider a compilation of humanity in terms of origins. It was highly ethnic and African-American,” Dr. Cooper says.

He names families such as the Pavliks, Grisniks, Podoliaks and other neighbors as influencing his early years, along with his five sisters and brother.

“I thought it was a very rich environment in coming to grips with where we were. It was a situation where we saw how people worked hard trying to survive.”

While his father “didn’t have a day of education and couldn’t read or write,” Dr. Cooper’s mother – with only nine years of education – instilled in him the importance of reading and staying informed as a means of rising above poverty, race, and ignorance.

That upbringing drove his passion for education.

“My mother was an avid reader and always had a daily newspaper and weeklies,” he says, crediting her as a major influence in his life and educational philosophy. “We were poor, but we were rich in terms of reading materials, which led to general discussions around the house. I think reading opened up for me new worlds, new ideas and discussions.”

His philosophy today on reading remains the same, even amidst the current political turmoil and racial unrest: “My message to you is that the book shall set you free, not the things you hear in the street. It will free your mind to achieve what you want to achieve as an adult.”

His father, meanwhile, taught him the love of the outdoors, which ignited his interest in science at an early age.

EDUCATION, ATTITUDE AND HISTORICAL MEMORY

Then there were his teachers, who further fostered his love of reading and science.

“I was always dedicated to reading, and they respected my interests,” he recalls, mentioning school librarian Miss Nixon by name. When he was 16, she encouraged him to read a biography of scientist George Washington Carver by Rackham Holt, which he says was a turning point for him regarding both his vocational interests and humanitarian attitude, particularly toward racism and the inequalities that so blatantly stemmed from that racism.

“In 1853, George Washington Carver was sold for a racehorse,” Dr. Cooper says, slipping easily into educator mode. “If a person like him can undergo an experience like that – a human experience of that magnitude with the intent to destroy – and still become one of the world’s great agricultural technologists, then I had to be of that same attitude.”

This is just one example of the importance Dr. Cooper places on education, knowledge and history in “elevating the human experience” across races, ethnicities, genders and religions without polarizing and dividing.

“I think education is very important because, if you have historical knowledge of any situation, it better prepares you for the human experience,” says Dr. Cooper, who has made this one of the tenets of his lifelong stewardship as a scientist and educator, as well as a civil rights leader and activist. “History is so important. A people without a historical reference or memory are doomed.”

SCIENCE AND ACTIVISM

After moving to Rochester with his wife, who was also a chemist, to complete a Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of Rochester, Dr. Cooper began a job at Eastman Kodak that would fuel a career as a research chemist and inventor. He is credited with three process patents in photographic chemistry, which he says is thanks to that company, which allowed Black scientists to succeed.

That falls in stark contrast, however, to an earlier interview experience he had with a large chemical company, which had sought him for a position after being impressed with his academic record. When the recruiter met with him in person and saw that he was Black, Dr. Cooper says the man seemed surprised, and his demeanor changed. Such incidents did influence his fight for civil rights, he says, but they didn’t deter him from pushing to succeed.

As such, he found himself settling long-term in Rochester, embedded in a community rife with civil unrest and civil rights activities. Even as he worked hard as an innovator at Eastman Kodak, Dr. Cooper would find himself drawn more and more toward the center of the civil rights world, emphasizing his humanitarian perspective and passionately held views that better education was the answer.

Along the way, he helped to found Rochester’s chapter of the Urban League and served as president of the Rochester chapter of the NAACP, which he says had more than 3,000 members, at least half of whom were white. In the early 1960s, he even took a leave of absence from Eastman Kodak to launch a new organization called Action for a Better Community in Rochester.

Dr. Cooper met Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1958 and had a couple of discussions with him about civil rights. “King gave a really nice talk dedicated to peaceful protest. It was a very brilliant talk,” Dr. Cooper says.

He says King emphasized the importance of being very disciplined and orderly to achieve success with a peaceful protest. Cooper later participated in a march on Washington led by King, and says it was “the most orderly march I’d ever seen.”

Dr. Cooper also had an opportunity to meet Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, whom he describes as a very interesting man, and he spent some time with Malcolm X, whom Dr. Cooper called “Big Red,” during his visits to Rochester in 1963. He also served on a committee with former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and knew Robert Kennedy.

At the center of Dr. Cooper’s civil rights activism, though, was his desire to improve education for Black people and other underserved children in Rochester and across the state of New York.

Connecting his activism with his education activities eventually led him to serve for many years as a member of New York State’s Board of Regents, which supervises all education activities in the state, from grade school to the state’s university system.

In 2010, the City of Rochester honored his many contributions to local education and named one of its local grade schools, Rochester City School Number 10, after him. The school now emphasizes research and interactive learning, which Dr. Cooper had promoted as a Regent.

W&J first recognized Dr. Cooper’s many accomplishments on behalf of education and civil rights in 1968 with its Distinguished Alumni Award.

He was 40 years old then. In 1975, Dr. Cooper was elected to W&J’s board of trustees, and he was named a trustee emeritus in 2000.

As W&J’s Dr. Knapp says of Dr. Cooper’s storied career and the many honors he has received, “The list goes on of accolades from those who know that our students will now have the opportunity for generations to come, to know about a man who is, indeed, an ideal role model for W&J students.”

In his speech to a small audience of W&J dignitaries, faculty, students, family and a few friends from Rochester as part of the dedication of the newly minted Cooper Hall, Dr. Cooper summed up his life’s mission of promoting education as a means of overcoming racial inequality.

“Life has been very good to me in a sense because I think I used lots of energy and time in promoting my own future and the future of the others around me,” he said to those gathered at the dedication ceremony. “That’s why I take a great interest in education, because it’s the leveling field for those who come from poverty, for those who are unnoticed in this great society. I have an undying commitment to try and to make life more promising and more pleasant for people who are in conditions of poverty and lacking much hope.”