When Samuel Willis ’98, M.D., talks to the medical students who shadow him at Baylor College of Medicine, he tells them that he never expected to be there.

“Growing up in Aliquippa, I never thought I would go to college,” Willis said. “It was never really a goal of mine growing up.”

Willis’s father dropped out of high school to work in the steel mill and was married at 17. He made a good living at the mill and was an elder in their church, but also struggled with alcoholism. Willis’s mother did graduate from high school, but didn’t push her children towards higher education.

“I thought I would be in Aliquippa, an elder or religious leader or working at a grocery store,” Willis said. “There were no high expectations for me to go to college or to go beyond college.”

He started considering a different path after high school when he heard from a W&J football coach, helping him realize that football could be a door to higher education. He applied to Howard University and was accepted, but the financial aid he needed to attend wasn’t available.

Willis was mentored by a physician working in his hometown who pushed Willis to find out more about the other college where he had been accepted. When he met with W&J’s financial aid staff, Willis realized college was within reach.

“It wasn’t a direct path, but I always felt like God was guiding me to that place [W&J],” Willis said. “I thought, this is a blessing from God to go to a really good school and learn. I took it seriously.”

Even though Willis was recruited for football, he didn’t play his first year. He had seen other football players from the Aliquippa area return home after their freshman year because of academic challenges and wanted to solidify his standing as a student before pursuing athletics. The football coaches supported his choice to focus on academics, and Willis joined the team his sophomore year.

The academic challenges were significant. Though Willis initally lagged behind in reading and writing, he put in the time and effort he needed to succeed.

“I said, if I have this opportunity I’m going to do the very best I can and I gave it my all,” Willis said. “That determination is something that you need when you are a child growing up in Aliquippa if you want to survive. It’s a survival type of mentality.”

His hard work paid off. Willis aced his first biology exam and got the attention of fellow students and professors.

His success in biology led him to the office of Dr. Dennis Trelka, who saw possibilities for Willis. He showed Willis the possibilities of a biology degree by having him shadow professionals in the field.

“I always had this interest in science, but I never knew this interest in science would lead to medicine,” Willis said. “It was Dr. Trelka saying, ‘you have this raw talent and you’re doing something good with it, but let’s direct you.’”

Outside of the classroom and the football field, Willis found a sense of belonging in the Black Student Union, eventually becoming the group’s president. There weren’t many minority students on campus at the time, and part of their mission under Willis was to bring awareness about black culture to the wider W&J community.

“It was a very interesting way for me to develop: this kid from a black neighborhood got dropped into a white environment,” Willis said. “But that whole environment helped create this tenacity that I have to drive me and push me to be ambitious and go forward.”

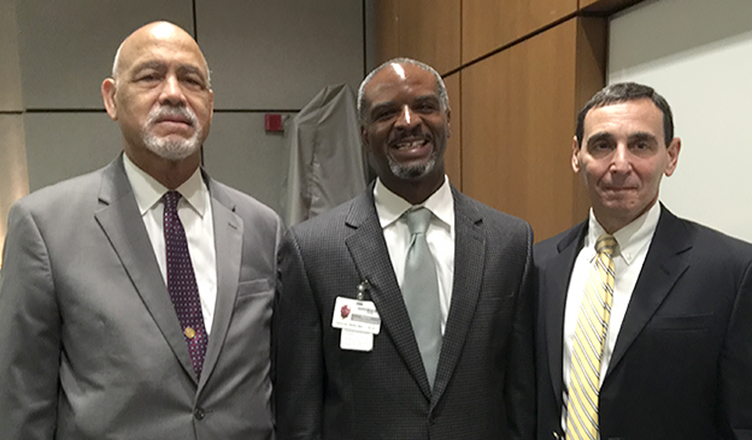

Trelka later introduced Willis to James Phillips ’54, M.D., and Gary Silverman ’78, M.D., Ph.D., both of whom also played football at W&J. These men helped chart Willis’ path to becoming a physician.

Silverman, who routinely hosts biology students from W&J as interns, took Willis on Trelka’s recommendation. Willis spent two summers interning with Silverman at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“He was a good, hardworking kid from southwestern Pennsylvania, and I identified with that quite a bit,” said Silverman.

Though Willis had low MCAT scores the first time he took the test, he worked to improve them by taking a review course during his second summer internship, all while staying in shape for the upcoming football season.

“He was fearless; he would just put his head down and do whatever he needed to do. I know a lot of kids would have given up a long time before he would have,” Silverman said. “He’s just a very strong character and a really compassionate guy.”

Phillips was employed at Baylor, recruiting underrepresented students to the medical school, and got Willis an interview.

“Everyone [I interviewed with] was certain that I would be a good doctor,” Willis said. “They saw my passion, they saw my sincerity, and they said ‘oh, he’s going to be a good doctor.’”

After he completed medical school, he decided against entering directly into a residency program. Instead, he joined the Peace Corps and spent two years in Burkina Faso as a health volunteer. He spent the first year learning the languages and culture and the second year working on health projects and developing a food bank to get the villagers through lean times.

While Willis was glad that he pursued the opportunity, it did mean that he was off cycle for his residency and would have to wait a year before he could apply. However, when Phillips found out that Willis had returned to the United States, he let him know that Baylor had a position available. Willis started his residency in family medicine just two months later, and joined the faculty of Baylor in 2007 upon completing his residency.

Five years ago, Willis became the medical director of Harris Health System’s Martin Luther King Jr. Health Center, a clinic serving primarily African-American and Hispanic patients without health insurance.

“I really enjoy what I’m doing. I feel like I’m making an impact on the patients I’m serving,” Willis said. “I feel like I’m doing God’s work, to me this is a ministry.”

Willis has come a long way from the undergraduate student who wasn’t sure how to talk to a potential mentor. Now he is helping to guide future generations of doctors, thanks to those who served as his mentors.